History

The history of the National Library reaches far back in time. What was originally a royal library is now everyone’s library.

From the King’s personal library to the National Library of Sweden, via censorship and the burning of a royal palace. Explore the National Library’s development throughout history.

Historical timeline

-

Dyalogus creaturarum moralizatus was the first book ever printed in Sweden. The National Library owns two copies. Written in Latin, it is a collection of cautionary tales and moral fables. These religious dialogues between the various creatures of creation provided preachers with good source material for popular teaching.

The book was printed in Sweden by the German book printer Johann Snell. His printing press was in Gråmunkekloster on the island of Gråmunkeholmen in Stockholm, now known as Riddarholmen. When it was published on 20 December 1483, it was already a bestseller in Europe.

Up until the year 1500, 16 books were printed in Sweden. A total of around 40,000 books were printed in Europe.

-

The book collections of the Vasa kings will form the basis of the National Library's collections. Their collections were stored in the Royal Palace, Tre Kronor ("three crowns").

King Gustav Vasa wanted his sons to receive an international Renaissance education and this required a library. Not only Gustav Vasa, but also his sons Eric XIV, John III and Charles IX helped build the collection of literature. Both Eric and John can be described as book collectors, and both took an interest in art and theology.

The first list of books in royal ownership dates back to 1568: the inventory of Eric XIV’s book collection drawn up by his teacher Benedictus Olai and the secretary Rasmus Ludvigsson at the time of Eric’s execution. This list is held in the National Library’s manuscript store under the reference U 201 and comprises 217 editions.

Today, not much remains of the original library, although our collections have been supplemented over the years by purchases, donations and spoils of war. This allows us to still attain good insight into 16th century literature.

King Gustav Vasa with sons, artist Hugo Hamilton, 1830.

-

The first Royal Librarian, Johannes Bureus, was appointed in 1611. Among other things, he left behind a large notebook called Sumlen. Sumlen is bound in a parchment from a medieval Latin manuscript and contains close to 700 pages.

The title National Librarian was first awarded on New Year’s Day 1910 to Erik W Dahlgren, who had worked as a head librarian since 1903.

The engraving depicting Johannes Bureus is made after an oil painting from 1627.

-

In her time as Swedish monarch, Queen Christina devoted a great deal of effort into establishing the Royal Library. In addition to large volumes from spoils of war, she acquired books, book collections and manuscripts. Price was not an issue. If she failed to acquire manuscripts owned by other libraries, she hired students in Europe who were given the task of transcribing them.

Christina’s library was very extensive for its time. It included literature on theology, rhetoric, history, language and other countries.

Books poured both in and out of the library. Christina shared generously with universities, high school libraries and her employees. When she moved to Rome in 1655, she also took part of the collection with her, not least some of the manuscripts. Despite this, the library possessed 5,590 printed books and 2,229 manuscripts at the time of her death.

Engraving of Queen Christina from 1653 or 1654. Artist: Sébastien Bourdon.

-

The Codex Gigas – also known as the Devil’s Bible – came to the National Library of Sweden as part of war spoils from the Thirty Years’ War in 1648.

The book was originally from a monastery in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic). In 1594 Emperor Rudolf II moved the Codex Gigas to his castle in Prague, where it remained until it was taken as booty at the end of the Thirty Years’ War by the Swedish Army, and brought to Stockholm. It was incorporated in the collections of Queen Christina of Sweden. In 1878 the work was moved from the Royal Palace Tre Kronor to the newly built National Library in Humlegården.

The portrait of the Devil is the most famous image in the Codex Gigas and is the source of the book's nickname

-

The first Legal Deposit Act was passed, requiring every printer to provide a copy of all printed publications in Sweden to the National Library, before the work was distributed.

The original intention of the act was censorship, a way for the king to control all publications before they reached the general public. Today, legal deposit regulations support the National Library’s work with collecting the Swedish national heritage. Without legal deposit, the National Library would not have become the abundant source of knowledge that it is today.

-

On 7 May 1697, the Royal Palace, Tre Kronor, burned down. Employees at the National Library, led by Johann Jacob Jaches, first carried but then threw books and manuscripts out through the windows four floors up in an attempt to salvage as much as possible. The result of the fire in the palace was devastating. Of 24,500 books and 1,400 manuscripts, only 6,000 books and 300 manuscripts could be saved.

To this day, many of the salvaged works have visible damage and still carry the smell of smoke left behind by fire.

Contemporary German engraving of the castle fire, 1694.

-

The National Library’s collections can finally move into the newly built Royal Palace of Stockholm, to the east wing where the Bernadotte Library is located today.

The reading room of 30 square metres housed all the activities, as it had heating facilities. All the other rooms were cold, damp and dark. The reading room was where librarians and caretakers worked. This was where all the tasks were performed; cataloguing, alongside taking receipt of printed matter. And members of staff had to share the space with visitors to the library.

One advantage was that the books now at least stood on shelves that were installed in the reading room and other rooms.

The Royal Library in the Royal Palace's north-east wing. Wood engraving after drawing by Otto Mankell, New Illustrated Magazine 1877.

-

Between 1865 and 1890, the National Library was governed by its most legendary manager of all time, Gustaf Edvard Klemming.

Klemming had been hired by the National Library back in 1844. Having held a number of prestigious positions, in 1865 he was put in charge with the title of Royal Librarian, a title that was changed to Chief Librarian in 1878. He stayed in this post until his retirement in 1890.

Klemming, who was himself a major collector, donated his own Swedish collections to the library. This amounted to around 10,000 volumes that he had collected since the age of 12. He was also a book connoisseur, medieval expert, handwriting researcher, prominent bibliographer and publisher.

His commitment to the library and its collections went beyond the ordinary. There was no boundary between the private person Klemming and the civil servant Klemming – he was constantly in the service of collecting books. These are his own words, in the Chief Librarian’s report for 1879:

“Prevented from spending time in the open air by prolonged chest problems, and from enjoying sleep in any way other than sitting in a chair during sparsely measured moments, every single day of the year have I been present at the National Library, and have thus been able to devote even more abundant time to the varying aspects of my work, finding within it at the same time my pleasure, my needs and my principal medicine.”

It was Klemming who drove the construction of the library in Humlegården, which is where he worked for the last 12 years in his position.

National Librarian Gustaf Edvard Klemming, Photographer: W Eurenius

-

In July 1871, the foundations were laid for what was to become the new library building in Humlegården. The architect was Gustaf A. Dahl.

Construction took seven years. The library was built by using modern materials and applying new technology. The cast iron structure was one of the first in the country. Thanks to this, they were able to create an open-plan solution and vast halls with high ceilings and larger windows with good natural light. The library was given a Neo-Renaissance façade, which was considered appropriate for a place of learning.

Most of the National Library has now been rebuilt, but the façade, the entrance and the great reading room are still the same – they have been given listed status and may not be changed.

The National Library in Humlegården, 1870s. Photo: Johannes Jaeger.

Humlegården

Humlegården was chosen because there were good opportunities to expand if more library buildings were needed. In addition, the area was state land as an old crown domain, which certainly made it easier.

Humlegården had previously been the kitchen garden of the Vasa kings. The name Humlegården comes from Gustav II Adolf growing hops (humle) there. Queen Kristina in turn created a baroque park. At the end of the 18th century, Humlegården became a park for the public.

During the first part of the 19th century, the park was an entertainment center with an inn and a theater. But in 1870s Stockholm, Humlegården and the areas around it had a bad reputation. The surroundings consisted of dirt and it was rocky and swampy. It was thought that with a library in the park, the slums would end, the problems would be built away.

-

The famous Swedish writer August Strindberg served as amanuensis at the Royal Library from 1874 to 1882. This was his only long-term post in the civil service and a merit that he would come to refer to many times throughout his life.

The National Library has a large amount of material by Strindberg, such as manuscripts, photographs, and, not least, books. He was a very prolific writer and there are about 4000 letters kept at the National Library that Strindberg wrote to friends, colleagues, his family and his publisher. The photograph below dates from 1875 when Strindberg was 26 years old.

August Strindberg in 1875. Photographer: G W Brunstedt.

-

On 9 November 1877, the National Library became an independent government agency under the Ministry of Ecclesiastical Affairs, and was formally named the National Library of Sweden. An administrative unit was also appointed: a chief librarian, two librarians and four amanuenses (administrative assistants) to serve in the library. The library was to be open every day except weekends and public holidays between 10:00 and 15:00, and all members of staff were expected to be on site. Members of staff were entitled to one and a half months’ holiday.

The mantra at this time was one that all the National Library employees are still familiar with and work according to: collect, describe, give access and preserve – although expressed in different words.

To be able to borrow from the library, a guarantor was required at this time. A book that had been borrowed could be kept for one month but was not leave Stockholm, unless permission had been obtained from the Chief Librarian.

-

The National Library in Humlegården opened to the general public on 2 January 1878. Gustaf A. Dahl was the architect.

It was the National Library’s caretaker together with the boatmen of the Royal Swedish Navy that took care of the move from the library in the Royal Palace of Stockholm to the new library in Humlegården. The move began in October 1877 and was completed at the end of the year. On New Year’s Day 1878, a caretaker used a sleigh to transport the National Library’s most famous manuscript and spoils of war, the Devil’s Bible, to the new library. The caretaker was accompanied by the royal librarian Gustaf Edvard Klemming, with two folios under his arm.

The gates were opened to the public on 2 January 1878. The library was open between 10:00 and 15:00. Initially there was gas lighting in the reading room, lending office and entrance. In 1887, electric lighting was installed in five study rooms, and in 1891 gas was replaced by electric light. The repository, however, did not have full electric lighting until 1964.

The Royal Library in Humlegården, about 1883. Photographer: Axel Lindahl.

-

Valfrid Palmgren Munch-Petersen (1877–1967), a pioneer in the library world, was the National Library’s very first female employee. It was in 1905, the same year that she defended her thesis in Roman Philology. She was employed as an extraordinary administrative assistant and worked in the lending office and the department of Swedish prints.

But her greatest contribution was to public libraries. In 1909, she was commissioned by the government to investigate the issue of public libraries and to propose how the state should best promote public library operations. Her ideas about library consultants and government grants for school libraries and municipal libraries were adopted and largely remained in place until the 1960s.

Valfrid Palmgren was also politically active, and in 1910 she became one of the first two women to take their place on the Stockholm City Council.

Valfrid Palmgren 1905, Photographer: Ferdinand Flodin.

-

On 1 January 1910, Erik Wilhelm Dahlgren (1848–1934) became the very first person to receive the title of National Librarian.

Prior to becoming head of the National Library, Erik Dahlgren had already been employed at the library a couple of times. In 1903 he was appointed Chief Librarian, a title that was later changed to National Librarian.

Dahlgren had a practical and organisational talent, and he set out to investigate how extensive the library’s collections actually were. According to his calculations, in 1903/1904 the National Library had 314,902 volumes and portfolios, as well as almost one million everyday printed items.

In addition to scientific works, Dahlgren wrote the book Min lefnad (My Life), in which he talks about matters including the work situation at the National Library at the time of the move to Humlegården.

-

The two new wings in the east and west opened in 1928. The architect was Axel Anderberg.

Construction started in 1926 and was completed in 1928 at a cost of around SEK 900,000. The extension meant more space for storage, a research reading room and more service rooms. The map collections now had their own place together with a repository, director’s room and reading rooms for visitors.

The new research and journal hall, which was just next to the old reading room, had been equipped with 30 research tables alongside 24 seats at long tables for short-term visitors, intended primarily for reading journals.

Preparations for the 1926 expansion.

The new research room was combined with a journal reading department.

-

Between 1956 and 1977, the National Library functioned as a humanities research library for Stockholm University College – from 1960 onwards known as Stockholm University.

-

Between 1956 and 1971, the library underwent extensive internal renovations and extensions in stages. The architect was Carl Hampus Bergman.

The National Library’s first underground repository was built on three storeys on the north side.

This renovation included a manuscript reading room on the ground floor and one for journals one floor up. The previous combined journal and research reading room was emptied of journals and furnished with a book gallery.

The basement was used for a restaurant, visitors’ toilets, catalogue rooms, photo department and more. Research carrells were set up in the basement of the east wing, available around the clock. Installed in the west wing were a Chamber of Rarities and a journal repository. The main reading room was restored and a new furnishing solution created 100 seats instead of about 65.

More visitors, more lending, major acquisitions — the history of the National Library has been a never-ending battle for space. The renovation had barely been completed before more space was needed. The solution was to allow staff to sit and work in the book collections.

-

At the initiative of National Librarian Uno Willers, in 1958 the National Sound Archive was established for the collection and preservation of audio documents. Initially deliveries were voluntary, but despite this the National Library managed to obtain most of what had been produced before 1955.

When the Swedish Legal Deposit Act was tightened in 1979 to include audiovisual material, the National Sound Archive was transformed into the new, independent government agency known as the Archive of Recorded Sound and Moving Images. The agency later changed its name to the Swedish National Archive of Recorded Sound and Moving Images, and it merged with KB in 2009.

-

The Rogge Library, which holds the collections of Strängnäs’ diocese and secondary grammar school library, merged with the National Library in 1968.

Rogge Library photographed in 1906. Photo: Municipal archive in Strängnäs.

-

The national union catalogue Libris was introduced in 1972. This marked the beginning of the digitisation of Swedish libraries.

In the 1960s, the research library faced new challenges, not least from the explosive increase in scientific publications. At the same time, computer technology was introduced as a universal remedy for processing large volumes of information.

The advent of Libris is best viewed in this light. The Swedish Agency for Public Management presented a vision of a completely integrated system that would handle all procedures for cataloguing, lending, acquisitions and checking journals.

In reality, this overall vision was to remain unrealised, at least initially. Instead there was focus on building a central database and developing functions for cataloguing, a not too simple task in itself.

In 1980, a crucial upgrade of the system was finally launched. It can be said that this is when Libris became established and a necessary part of the research library’s activities. Today Libris is available to public libraries.

In 1988, KB was given total responsibility for its operation and development.

The new Libris was launched in 2018. The format of this is based on Bibframe 2.0 and open linked data. This means that not only the library’s users, but also internet search engines will find and understand our library information in a completely new way.

A Xerox Alto computer from 1972.

-

The Legal Deposit Act is expanded to include film, music, radio, TV and multimedia.

-

Birgit Antonsson became Sweden's first female National Librarian in 1988. She was first employed as a library council at the National Library in 1987 and was then chosen as National Librarian in 1988. She held this position until 1995 when she became Director-General of the Ministry of Education.

-

Between 1992 and 1995, two underground repositories, each of 9,000 square metres, were built under the National Library.

Starting in 1992, blasting created caverns located 40 metres below ground level and 25 metres below the groundwater surface. The blasting was completed in November 1993. By then, 110,000 cubic metres of solid rock had been driven out through the transport tunnel, in more than 33,000 truck loads.

The repositories are built of prefabricated concrete panels and are installed as freestanding buildings, each with five storeys. Each repository is 150 metres long and 13.5 metres wide. The two buildings have a total storage space of 160 shelf kilometres, which – as things stand at the time of writing – is expected to last until 2050.

The first underground repository was completed in November 1994 and the second one in 1995. The repositories are connected to the main building via lifts and stairs.

-

In 1995, the Legal Deposit Act was applied to video games and interactive media.

-

Between 1995 and 1997, the main building was further renovated and an annex added.

Major modifications were made in the original building. With two new underground repositories, the old repositories could be converted into office premises. Virtually everything has been rebuilt, except the parts that have been listed since 1935: the large reading room with its cast iron columns and decorative painting, the marbled entrance hall and the plastered Neo-Renaissance façade.

The annex, which is located at the back of the National Library, is a transformation of the first underground repository dating back to the 1960s. This created a great deal more space for visitors, with an auditorium for about 130 people and new reading rooms.

The Public Art Agency Sweden (Statens konstråd) assumed responsibility for the artistic decoration following the redevelopment, based on the notion that art should be integrated into the architecture, both inside and outside.

Architects: BSK Arkitekter AB and Jan Henriksson Arkitektkontor. Artistic decoration: Einar Höste (outdoor park side), Sivert Lindblom (outdoor entrance side); and indoors, Harald Lyth and Nils G. Stenqvist.

The National Library seen through the glass annex.

-

In 1997, the National Library starts collecting Swedish websites in the cultural heritage project Kulturarw3.

In early 1996, there was a discussion around the coffee table at the National Library about the development of the internet. It was confirmed that some of what had previously been published in print was now being published on the internet instead. Moreover, some of this was removed after a relatively short period of time and was thus lost to future research. This was the basis of the notion that Swedish publications published on the internet should also be preserved for posterity. Not long after, the Kulturarw3 project was launched.

When the collection process began in 1997, the National Library was among the first in the world to undertake this kind of activity.

-

In 2004, staff at the National Library discovered that several books were missing. This marks the beginning of extensive inventory of the library’s collections. It was ultimately confirmed that 62 of the library’s older and more valuable books had been stolen, and that the thefts had been going on systematically over a period of nine years (1995–2004).

It turned out that the culprit had been employed as senior librarian at the National Library. To be able to sell the books on abroad, he manipulated them. For example, he concealed the provenance of the books, their unique history, by scraping away signatures and cutting up pages.

Since this discovery, active efforts have been underway to try and recover the stolen books. At the time of writing, 17 books have been returned to the National Library.

-

Mass digitisation of audiovisual media such as radio, television, music, film, audiobooks and video games began in 2005.

Digitisation is used as a method of preserving the library’s collections and accessing them regardless of location.

One important reason for digitising audiovisual material, is that older material that exists only in physical form will be lost. Partly because the life span is sometimes short, such as for audio cassettes and VHS tapes, and also because the equipment that can play back the material is quickly disappearing from the market. Old devices are difficult to maintain and will be difficult to use in the future.

-

Astrid Lindgren’s personal archive was inscribed on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register. This honour is bestowed upon archives, museums or documents that are considered to have value for all mankind.

The Astrid Lindgren Archive covers 150 shelf metres and is among the most comprehensive that a Swede has ever left behind. In the archive you will find everything associated with Astrid Lindgren’s long career as an author. There are lots of letters, manuscripts for books and films, press clippings from Sweden and other countries, and photographs from her theatrical productions. One slightly more cryptic part of the archive is the 600 stenogram blocks with Astrid Lindgren’s original manuscripts.

You can explore the archive in the Arken database. External link.

Photo: Pål-Nils Nilsson.

-

The two government agencies, the National Library and the Swedish National Archive of Recorded Sound and Moving Images, merged to form one joint agency in 2009.

The merger meant the National Library has a new function as both national library and archive for sound and image.

It was the two heads of the agencies, Gunnar Sahlin from KB and Sven Allerstrand from the Swedish National Archive of Recorded Sound and Moving Images, who brought up the idea of a merger. The Ministry of Education did not hesitate. Parts of the instructions for the Swedish National Archive of Recorded Sound and Moving Images were incorporated into the National Library’s instructions, with clarifications about acquisitions, care and pruning.

Thanks to the mass digitisation of audiovisual media at the Swedish National Archive of Recorded Sound and Moving Images, the National Library’s digitisation skills received a boost.

-

%20Filmarkivet_Grangesberg_2014.jpg)

In 2011, the National Library took over the activities of the Archival Film Collections in Grängesberg, a cultural history archive of the films of the Swedish people.

Since 2003, the Archival Film Collections – formerly part of the Swedish Film Institute – has received donations of films from associations, companies, municipalities, archives, museums and private individuals. The films are non-fictional and reflect various aspects of the 20th century, with an emphasis on the years 1930–1980. They are not intended for viewing at the cinema.

On November 1, 2024, Grängesberg was discontinued as an active operational location. The task of collecting, organising, and digitising non-fiction films on film stock was subsequently integrated with the National Library’s other activities.

%20Filmarkivet_Grangesberg_2014.jpg)

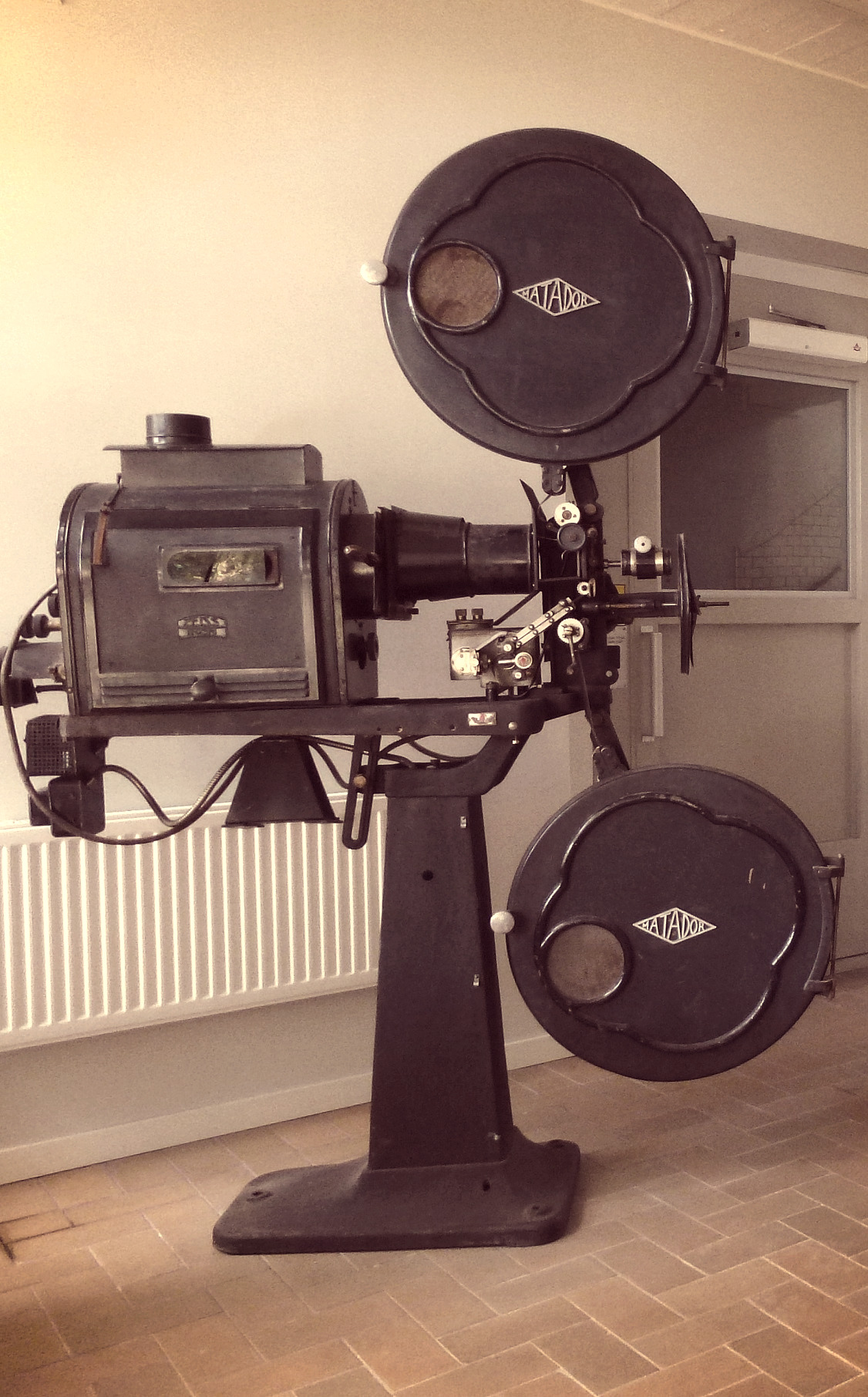

This film projector is in the Film Archive in Grängesberg

-

The Legal Deposit Act for Electronic Material (2012:492) was introduced in 2012. The legal deposit regulations now made it possible to collect digital material published for the general public in Sweden. The act came into full effect in 2015.

-

In 2014, the National Library started digitising all Swedish newspapers published in Sweden.

Since 2010, the National Library and the Swedish National Archives have been collaborating on digitisation and have established a large-scale production line for the digitalisation of newspapers and magazines.

Older titles, as well as new material for titles that are still being published, are constantly being added to the library's large collection. At present (2018–2023) there is a major initiative to digitise and give access to newspapers from 1734 to 1906.

-

In 2015, the National Library receives a government assignment to create and formulate a national strategy for the Swedish library sector.

-

The Dag Hammarskjöld Collection was inscribed in UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in 2017. This honour is bestowed upon archives, museums or documents that are considered to have value for all mankind.

The collection covers approximately 45 shelf metres and includes everything from documents on world politics to private letters and newspaper clippings. Most of it is in English. The material provides a valuable insight into the period following the World War II and the Cold War era. The UN part of the collection is digitised and can be accessed in the Peace Archive External link..

Explore the collection in the Arken database. External link.

Photo: FN

-

The National Library submits a proposal for a national library strategy to the government in 2019. The proposal includes investments in school libraries, national minorities and digitisation. The starting point is the section “Libraries for all” from the Swedish Library Act.

-

In 2019, KBLab is founded. It is a national research infrastructure for digital humanities and social science. Through the lab we provide access to the National Library’s collections in structured and quantative form. This makes it possible for researchers both to seek new answers and pose new questions in their research.

One example of research from KBLab is the language model BERT, which can read and understand texts – from newspapers to literature.

-

In 2022, the government adopted a national library strategy for Sweden and gave the National Library a new assignment: to suggest how collaboration in the Swedish library sector can be strengthened, as well as to contribute to the long-term development of certain national digital library services for prioritised target groups.

-

The Swedish Freedom of the Press Ordinance of 1766 is inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of he World Register. The first of its kind in the world, it comprises two parts:

- The right for all citizens to publish thoughts, opinions and emotions in print.

- The right for all citizens to have access to public agencies’ and governing bodies’ records (for example decisions, meeting minutes, and public inquiries), and publish them in print as desired. This right is called the principle of public access to official records.

These unique primary source documents are preserved at the Swedish National Archives and the National Library of Sweden. By studying records housed at the Swedish National Archives we can follow the drafting process for the Freedom of Press Ordinance, and together with printed materials at the National Library of Sweden are able to follow the consequences of implementation of this new legislature.